Thanks to archival records, we now know that the Basques were among the first Europeans to engage in regular commercial whaling in the waters of the St. Lawrence River. One notable site is the wreck of the San Juan de Pasajes, a Basque ship that sank in 1565 at Red Bay, Labrador, 80 km east of Blanc-Sablon.

Early maps dating from the 15th century show land to the west with the name Bacalao, which is an Iberian name for cod. It is possible that the Basques followed the Vikings, before the 14th century, along their journey to the western shore of Greenland. Basque whaling is generally thought to have moved from the Basque coast via Iceland around 1412 and then to Newfoundland.

It is certain that in 1517, a ship commanded by a Basque captain left Bordeaux for the New Lands to fish for cod. According to historical documentation, Basque expeditions to the Gulf of St. Lawrence appeared in 1517 and was largely supported from 1530 onwards by financing and insurance structures developed in Burgos. It is thought that the first ships were here for the cod and then they became more interested in the whales.

As of the 1580's the Spanish Basque whaling trade began to decline. After several prosperous and adventurous centuries, ships were returning to port half-empty. King Philip II's demands on Basque participation in his Gran Armadas, placed a heavy burden on experienced Basque sailors and, subsequently, on their whaling activities.

The 17th century saw a slow decline in the Lower North Shore fishery.. Basque people joined the transatlantic expeditions on French, Spanish and even Dutch ships documented for the 1620s and 1630s

By 1600, there was almost no whaling in Labrador, and the Basque moved further south to Tadoussac, as documented by Samuel de Champlain. Red Bay was considered one of the favourite locations. It welcomed around 900 people a year, and in 1575 - 11 whaler ships were in port. A ship had a crew of 50 to 120 people. Every year some 2,000 Basques were busy fishing in the St. Lawrence River.

The Basques also hunted seals and walrus, and harvested whale baleen, a material that was the plastic of the day for making corsets, sunglasses and parasols. Basque whalers disappeared from the Gulf of St. Lawrence after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht, following the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713.

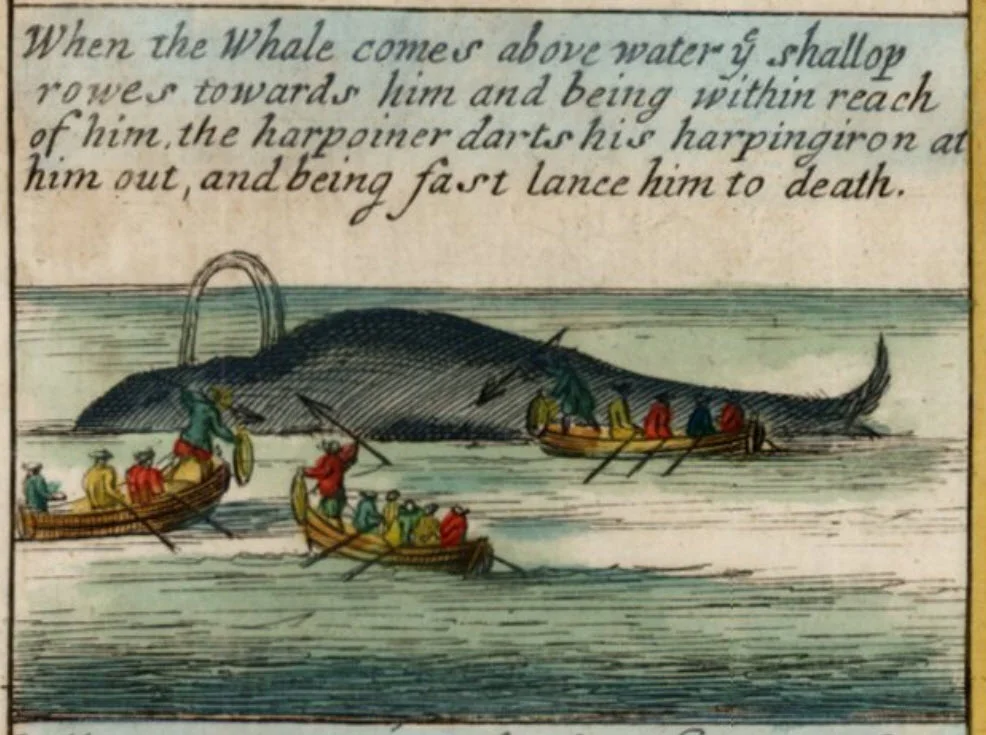

The whalers - galleons - were almost always bigger and better equipped than the cod ships. As many as 120 men boarded the whaler and these men often came from across a large span of territory as there were never enough men available in one city to outfit a galleon.

While the complications of outfitting a whaler were considerable, the rewards were enormous. On the larger ships, over 1,000 barrels of whale oil were brought back. This cargo was worth a minimum of 6,000 ducats. 100 ducats a month was considered a rich man's wage. This all depended on whether the oil was sold locally or in Flanders, France or England. Spanish cod-fishing trips also made a profit, however this was not comparable to the whaling trips. Cod was almost always intended for a domestic market.

The Basques also hunted seals and walrus, and harvested whale baleen, a material that was the plastic of the day for making corsets, sunglasses and parasols. Basque whalers disappeared from the Gulf of St. Lawrence after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht, following the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713.

In 2001, the Basque site Hare-Harbour 1 (EdBt-3) was discovered by the Smithsonian’s Arctic Studies Center which was conducting an archaeological survey of the Quebec Lower North Shore (LNS) from the Mingan Islands to the Strait of Belle Isle. The Gateway Project, as it is named, has many goals, the first one being the exploration of the region and identifying new archaeological sites for further studies. Over the years, the project discovered hundreds of new sites from a complete maritime archaic long house to a 19 th century fishing and trading post and occupations from all the prehistoric and historical cultures present on the coast between those dates, except maybe Viking occupation.

Archaeologist M. Erik Phaneuf

In 2003, a local diver and friend of the Gateway project in Harrington Harbour did a preliminary dive at the site and reported the presence of numerous roof tiles, some whale bones as well as recuperating large pot fragments found lying at the bottom.

Some artifacts from the 19 th century seal fisheries and other pot fragments and whale flipper bones from the Basque occupation were observed still lying at the bottom. It became obvious that numerous ships were anchored at the same time in front of the terrestrial Basque site (Fitzhugh, Chretien, Sharp and Phaneuf, 2006).

The whalers - galleons - were almost always bigger and better equipped than the cod ships. As many as 120 men boarded the whaler and these men often came from across a large span of territory as there were never enough men available in one city to outfit a galleon.

While the complications of outfitting a whaler were considerable, the rewards were enormous. On the larger ships, over 1,000 barrels of whale oil were brought back. This cargo was worth a minimum of 6,000 ducats. 100 ducats a month was considered a rich man's wage. This all depended on whether the oil was sold locally or in Flanders, France or England. Spanish cod-fishing trips also made a profit, however this was not comparable to the whaling trips. Cod was almost always intended for a domestic market.

The Basques also hunted seals and walrus, and harvested whale baleen, a material that was the plastic of the day for making corsets, sunglasses and parasols. Basque whalers disappeared from the Gulf of St. Lawrence after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht, following the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713.

M. Erik Phaneuf has been active in archaeology for more than 30 years with experience in historic and prehistoric, classical and urban archaeology and underwater archaeology in Quebec, France and Portugal. He has worked for numerous years for different cultural resource and heritage management firms in the province of Quebec.